At the end of my last post, I promised a bit of good news in my next Substack.

No, there is not a miracle cure for Parkinson’s.

But from my point of view, this is sort of the next best thing.

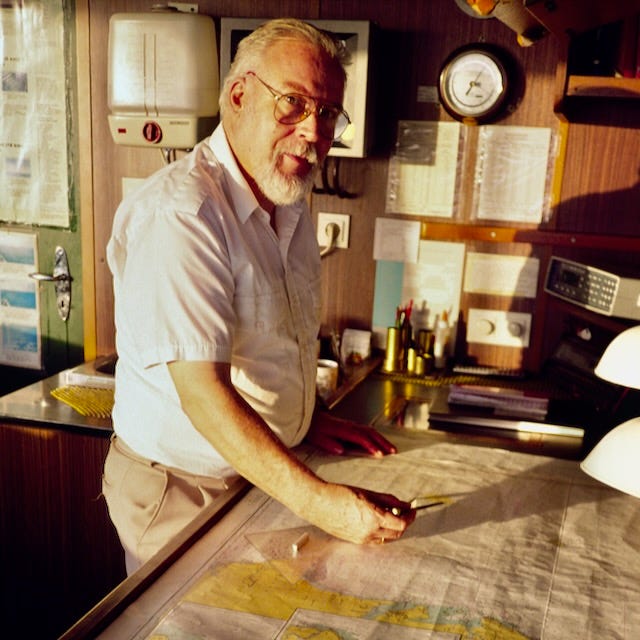

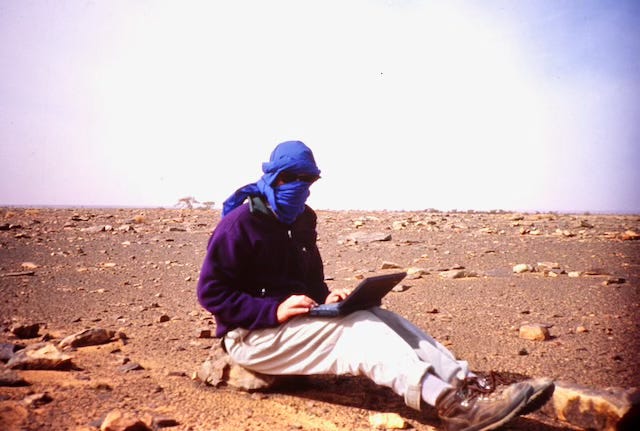

Over the course of these posts I’ve often alluded to the nine-month journey I undertook in 1993/1994, attempting to circle the world without airplanes as a devotional kora (a pilgrimage in the form of a circumambulation) around planet Earth.

The book I wrote about that epic trip — The Size of the World: Once around without leaving the ground — was published in 1995 by Globe-Pequot Press. It got some pretty good press:

“Greenwald has produced a travel book like no other.... His tale of the journey is an armchair delight for its originality, humor, and striking prose.... Funny and engaging, this is one-of-a-kind travel literature.” - Publishers Weekly (starred review)

and...

“Fabulous and fascinating... The Size of the World deserves to be compared to some of the classics of travel literature, including Robert Byron's The Road to Oxiana and Graham Greene's Journeys Without Maps.” — Jonathan Kirsch, Los Angeles Times

Still, I think it pays to remember Woody Allen’s observation: “I cannot abide by the judgment of other people, because if you accept it when they say you deserve an award, then you have to accept it when they say you don't.”

Case in point: Publishers Weekly’s lacerating review of my beloved book Snake Lake, with insults so arcane (e.g., “feckless” and “callow”) that I had to look them up.

But back to Size of the World.

This Spring, thanks in large part to a devoted reader in Los Angeles, the book will be released in a 30th (i.e., pearl) Anniversary Edition. The new printing will include an up-to-date Introduction, a Foreword by my beloved friend and editor Donald W. George, and a surprising appendix. It has been a very, very exciting process to bring this book back to life. My hope is to introduce one of my very favorite “offspring” to a new generation of readers — readers who may not even have been born when the journey took place, and who probably don’t know that, in the course of writing the book, I became the first travel writer to publish “blogs” (five years before the word was coined) on the World Wide Web.

This new edition of The Size of the World will be self-published, which means that it will be available via print-on-demand through this portal or from me directly. I’ll let you know when it’s hatching. Meanwhile, My friend Laurie Wagner (the wonderful Wild Writing coach with whom I co-lead the Himalayan Writers Workshop in Nepal every November; 2025 dates TBD) suggested I offer some samples from the book. So let me share this segment — The Paradise of Oranges — with you today. (Sally Knight, by the way, was my traveling companion.)

The Paradise of Oranges

“You know you’re in a wealthy city,” Sally observed, “when the orange trees still have fruit on them.”

But the word “fruit” was inadequate to convey the richness of Marrakesh’s urban arbors. It wasn’t a question of a few stray globes hanging over the clean sidewalks. Banquets of oranges weighted the limbs of the trees lining Avenue Mohammed V, fluorescent against red clay walls, ripening against an animated backdrop of buses, taxis and horse- drawn cabs.

Marrakesh is a phenomenon unto itself. The city is to shopping what Louis XIV was to interior decorating, what Edison was to electricity, what Miami is to blue hair. The medina, with its labyrinthine souks, claims to be the largest open-air shopping arcade in the world, and I could not imagine that a more impressive display of on-sale commodities exists, or needs to exist, anywhere. For the career shopper Marrakesh has always been a kind of mecca, a place of once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage where the divine excesses of the discipline are preserved and practiced in their purest, most sanctified form. It makes the soulless, philistine shopping malls of America look like vending machines.

You can buy giant snapping turtles that wander purposefully out of their cages and onto the pavement, saved at the last minute by some attentive passerby as they are about to saunter beneath the wheels of an approaching truck. You can run your hands through bins of rainbow potpourri, necklaces made of cloves, stones that produce aphrodisiac incense when they’re burned. You can examine silver daggers in inlaid alabaster sheaths and chess sets of sharply scented Moroccan cedar. You can try on supple leather slippers with colored rhinestones glittering on their toes, silk burnouses with intricate embroidery racing around their collars and cuffs, and Chicago Bulls baseball caps.

You can juggle gigantic pottery vases that look just like the one the Zork lives in in One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish and balance gigantic serving trays made of brilliant chased brass on your head. You can find Brazilian coffee, French pastries, Chinese umbrellas, Korean ginseng, Spanish omelets, Indian incense, Swiss watches, Japanese cameras, Belgian chocolate, Malian pendants, South African diamonds, English cricket bats, German facial creams, ice cream bars from the Canary Islands, pharmaceuticals from Saudi Arabia and American cigarettes. You can buy forty-seven varieties of olives.

We encountered an old Arab man selling socks. They were decorated with Halloween motifs: jack-o’-lanterns interspersed with grinning white skulls. We instantly awarded him the prize for Most Culturally Dissonant Commodity.

“Excuse me,” Sally said, approaching the merchant with a smile. “Do you know what those decorations are?”

He studied the socks and turned back to her confidently. “That is the world,” he said, pointing to a pumpkin, “and here is the head of a slave.”

Though the medina was spectacular, it was not where I worshipped. Just to the west of the Jamaa el Fna — the inscrutably named “Place of Nothing” where the clowns and dentists and storytellers perform — the city’s orange sellers ply their trade.

There are dozens of them, positioned behind broad wooden tables sagging under the weight of their cargo. Millions of huge, sweet oranges, the pride of Morocco, rise in four-sided pyramids toward the sky, half obscuring the red-cheeked, thick-wristed men who split and pump them dry in tough chrome squeezers. For 2 dirhams —18 cents — one is handed a tall clean glass filled to the brim with fresh, cold orange juice so perfect and honest and sweet that you burst into tears drinking it.

Here, at last, is the Platonic ideal, and everything you’ve had before — everything else called “orange juice”— has been but a lame attempt to imitate it. Thank God for oranges, you cry, downing your first glass. Thank God for Morocco, and the planet Earth! After two glasses you are deliriously happy; after six glasses you’re whirling like a dervish, spinning wildly through the Jamaa el Fna, spinning in a beatific citrus ecstasy while blind Moroccan beggars toss coins into the empty glass still clutched in your hand.

It’s interesting to look back on that book, and that journey, from my current perspective. Needless to say I am not able to undertake (or even contemplate) such an adventure today. There was a wonderful moment, 12 years ago, when Google came within inches of sponsoring a sequel adventure, during which I would have retraced parts of my route (flying this time) to reunite with five of the most colorful characters in my book and — using Google Glass’s recording features — interview them about how new technologies were impacting their lives. But on the eve of the proposal’s green light, Google dropped Glass, and that dream shattered. So it goes.

When I think about my previous life as a traveler today what comes up for me is not resentment or bitterness, and certainly not self-pity for the reduction of my peripatetic former life. Yes, it would be wonderful to visit Paris (I haven’t been there in ages) and stroll along the Seine, or return to New York City and cap a walk along the High Line with a visit to the Whitney. I can no longer do such things, at least not with any ease.

But the truth is, even as I write those words I don’t believe them. Call it denial, call it hope, but part of me refuses to accept what I’m experiencing as a life sentence. I abide with the conviction (or perhaps delusion) that a corner will be turned and that — during my lifetime — there will be a miracle cure. Or at least a procedure that addresses the pathology in my hip and lower back, and makes long walks, on urban sidewalks or mountain trails, possible again.

Then I’ll really have some good news to share.

Meanwhile, I think most of you know my drill: to do what I can do while I can do it, then do something else. And always, with gratitude.

Jeff, after 6 months of filing all of your posts (except your new year's post that I read first when it came out) into a reading file, I have finally read them all. My husband was diagnosed with PD last summer and your friend Kate referred me to you. I wasn't ready to read them as we transitioned to the news of his diagnosis. Now we are on a sun-break from Amsterdam and have been in Thailand for 3 weeks. I have been able to give them all the attention they deserved and read each one. I have enjoyed your stories from your travels and found how you weave in the challenges you face now with your life today while taking us on your very interesting journey in the past years. The NO WHINING ON THE YACHT has become my daily mantra and I have shared it widely. Like you, I know how privileged we are in this scary world we are in today and feel so fortunate to have been born in the 50's and experienced the US in the 60's-90's. Most importantly, I asked my husband to read your posts and he did. We can no longer bury our head in the sand, and like you, "we're not done yet." Thank you again for sharing your many stories and reminding us that PD is only one part of all of our stories

Thank you for taking us with you into this abundantly rich place. I don't know that I'll ever actually go, but after reading these passages, I feel as though I've been. Beautiful.