“I have often said that laughter is carbonated holiness, and the effervescent Wes Nisker is one of my favorite Holy men ever.”

- Anne Lamott, from her Foreword to The Big Bang, the Buddha, and the Baby Boom

Sometimes we have close friends who are also our spiritual teachers. That’s what Wes “Scoop” Nisker (1943-2023) was to me. He probably would have laughed if I’d told him that. He wasn’t preachy or starry-eyed, or any kind of guru. He was just someone who — along with drinking bourbon, cheering on the Warriors or watching Marx Brothers films with — I could turn to for guidance when my life or emotions seemed to be veering out of control. Which happened a lot.

I wasn’t the only one he did this for. Along with being a legend in the radio world Wes was also a beloved teacher at Spirit Rock Meditation Center, where his signature blend of wisdom and comedy suggested Thich Nhat Hanh performing a Firesign Theater sketch.

A trio of things brought Wes to mind as I prepared to compose this beginning-of-winter Substack offering. The first was a poem he wrote in 2006 – more like a list-in-verse – for a Buddhist journal he co-edited, The Inquiring Mind. I’d forgotten about the poem until a friend read it aloud at a recent dinner/poetry gathering, and it reminded me why I too (all of us, actually) might want to spend some time on the zafu (cushion).

Why I Meditate (after Allen Ginsberg)

© 2006 by Wes Nisker (from the Fall 2006 Inquiring Mind)

I meditate because I suffer. I suffer, therefore I am. I am, therefore I meditate.

I meditate because there are so many other things to do.

I meditate because when I was younger it was all the rage.

I meditate because Siddhartha Gautama, Bodhidharma, Marco Polo, the British Raj, Carl Jung, Alan Watts, Jack Kerouac, Alfred E. Neuman, et al.

I meditate because evolution gave me a big brain, but it didn’t come with an instruction manual.

I meditate because I have all the information I need.

I meditate because the largest colonies of living beings, the coral reefs, are dying.

I meditate because I want to touch deep time, where the history of humanity can be seen as just an evolutionary adjustment period.

I meditate because life is too short and sitting slows it down.

I meditate because life is too long and I need an occasional break.

I meditate because I want to experience the world as Rumi did, or Walt Whitman, or as Mary Oliver does.

I meditate because now I know that enlightenment doesn’t exist, so I can relax.

I meditate because of the Dalai Lama’s laugh.

I meditate because there are too many advertisements in my head, and I’m erasing all but the very best of them.

I meditate because the physicists say there may be eleven dimensions to reality, and I want to get a peek into a few more of them.

I meditate because I’ve discovered that my mind is a great toy and I like to play with it.

I meditate because I want to remember that I’m perfectly human.

Sometimes I meditate because my heart is breaking.

Sometimes I meditate so that my heart will break.

I meditate because a Vedanta master once told me that in Hindi my name, Nis-ker, means “non-doer.”

I meditate because I’m growing old and want to become more comfortable with emptiness.

I meditate because I think Robert Thurman was right to call it an “evolutionary sport,” and I want to be on the home team.

I meditate because I’m composed of 100 trillion cells, and from time to time I need to reassure them that we’re all in this together.

I meditate because it’s such a relief to spend time ignoring myself.

I meditate because my country spends more money on weapons than all other nations in the world combined. If I had more courage, I’d probably immolate myself.

I meditate because I want to discover the fifth Brahma-vihara, the Divine Abode of Awe, and then go down in history as a great spiritual adept.

I meditate because I’m building myself a bigger and better perspective, and occasionally I need to add a new window.

Our first meeting in 1985, as I now probably mis-remember it, was providential. My friend Stef and I had wandered into the now-defunct Cody’s Books on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. On the other side of the store stood a man with an almost rabbinical countenance and close-cut, fuzzy black hair, chuckling out loud over a book he’d picked up from the non-fiction table.

“That’s Scoop Nisker,” Stef whispered to me. “He’s a famous local radio commentator. You guys would probably like each other; let me introduce you.” As we approached, we saw what Wes was reading: It was Mr. Rajas’s Neighborhood, my newly released first book about Nepal. And so began our long friendship.

We evolved, in some ways, together, at least artistically. Both of us published books (His Crazy Wisdom, my Shopping for Buddhas) that approached spiritual practice with reverent irreverence. And during the early 2000s we both wrote and staged one-man shows at The Marsh in San Francisco. Wes’s offering, The Big Bang, the Buddha and the Baby Boom, simultaneously profound and hilarious, sold out nearly every performance.

His legacy — in videos, radio recordings, books and dharma talks — is enormous, as a look at his website will show. Here’s a bit extracted from one of his gigs at the Throckmorton Theater, where he breathes new life into a notorious New Age trope: “Everything is Everything.”

During one run at The Marsh we shared the same stage; he performed his show at five p.m., and I followed with Strange Travel Suggestions at eight. I’d often show up early to watch his act. It was a joy to be embedded in his audiences, howling with glee as he deconstructed the human condition with the bemused alacrity of a future anthropologist.

“As you may have heard, we no longer regard space and time as separate dimensions. They are as inseparable as up and down, light and dark, left sock and right sock. Time and space are now spacetime. Where you are is also when ... which makes ‘be here now’ redundant.”

- Wes Nisker, from Crazy Wisdom Saves the World Again

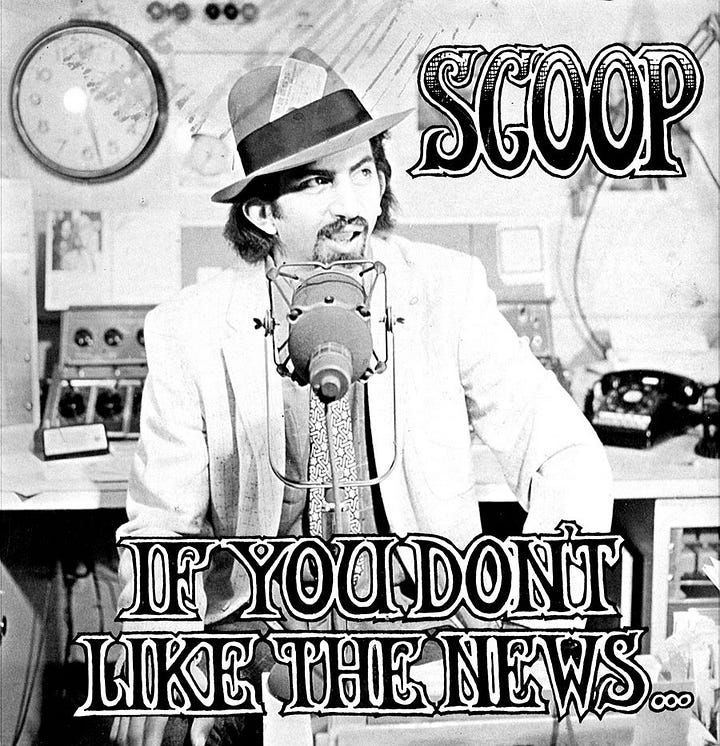

Wes is the subject of this post for a couple of other reasons as well. For one thing, tomorrow – December 22, 2024 – would have been his 82nd birthday. (Happy Birthday, Scoopji, wherever you aren’t.) The second is because the Winter Solstice is upon us and, as a pioneering news radio-with-a beat journalist (first for KSAN and later KFOG), Scoop’s take on the cosmos in general, and our planet in particular, was always a slyly enlightening mix of sermon and science. Here is a live recording of Wes on KFOG in 2002, delivering in manic but flawless cadence a whole bunch of messages still scarily relevant today.

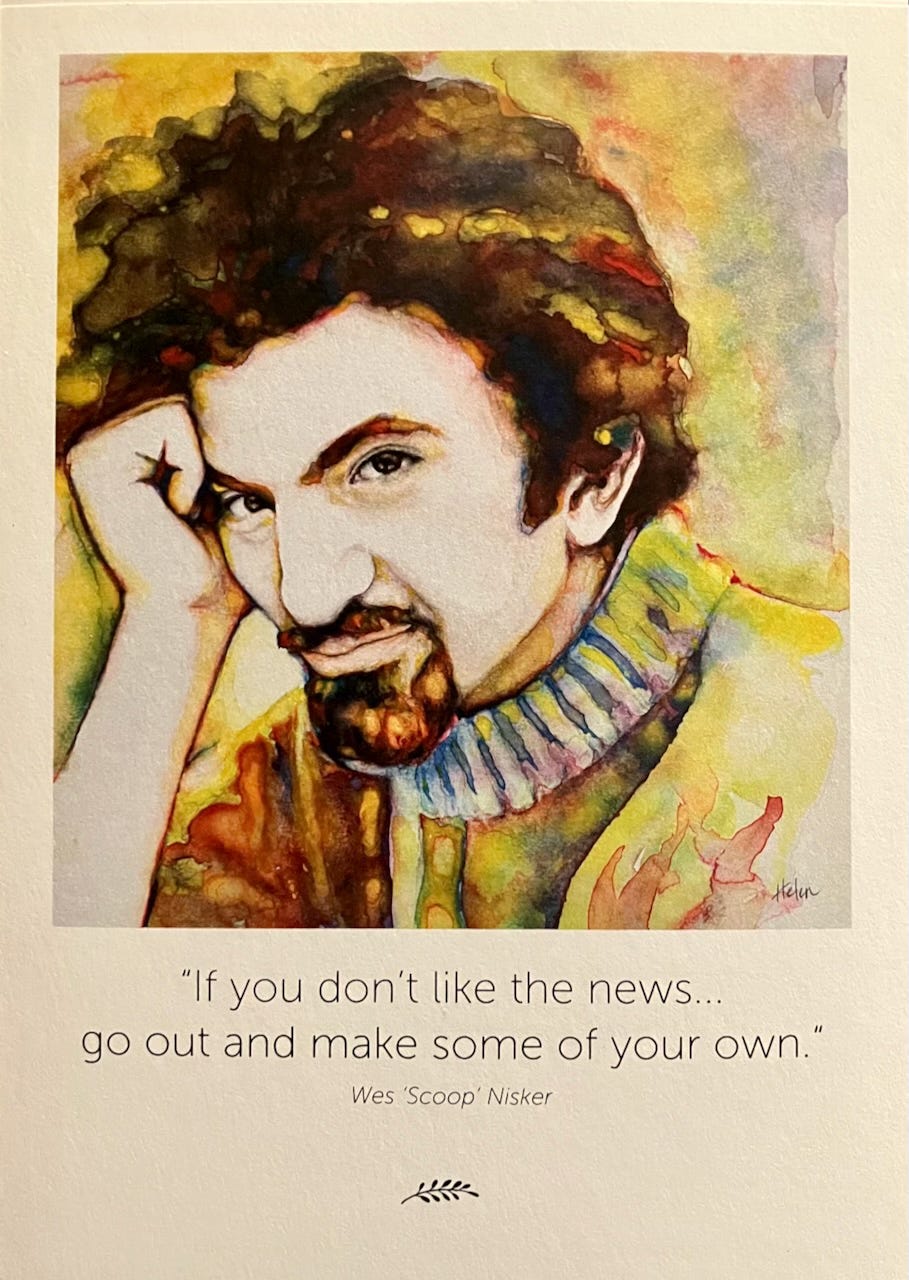

Most relevant of all, though, was his signature sign-off: a phrase that became so widespread that, on the many occasions when we sat together at a sidewalk café, passers-by would see Scoop and slow their steps, intoning his mantra:

“If you don’t like the news ...Go out and make some of your own.”

We don’t. And we will.

(For a wonderful tribute to Wes, read Perry Garfinkle’s thoughtful eulogy in The Oaklandside.)

Long before his diagnosis, I noticed the tremor in Scoop’s hands as he passed me my goblet of Kentucky bourbon. Such tremors are not uncommon as people age, and Wes was by then well into his 70s. But his “Parkinsonian-like symptoms,” it turned out, signaled neither normal aging nor PD. They were the first inklings of Lewy body dementia—a progressive neurological disease that also impacts the body’s ability to produce dopamine.

LBD is not the same as Parkinson’s, but they’re closely related: LBD causes some or all of the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. (What this means for me, with my own mobility issues, I hesitate to speculate.) More than a million people in the U.S. are affected by LBD, which also causes problems with learning and memory – as well as auditory and visual hallucinations.

The cause of LBD is well established. It is, according to the National Institute on Aging, “associated with abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein in the brain.” These deposits, called Lewy bodies, affect two of the brain’s neurotransmitters: acetylcholine, which impacts learning and memory; and dopamine, which affects just about everything else.

In Wes’s case, obvious lapses in cognitive function and memory were the first symptoms. He often called me up in confusion, asking me to teach him an easy computer function (like creating a new desktop folder) that I’d showed him several times before. Or we’d make a plan to meet that day for lunch, and he’d call repeatedly to be reminded which day it was.

But not all his symptoms, his health care advocate later told me, were a cause of frustration. One indicator of Lewy body dementia is pronounced hallucinations – and Wes had these. Several times during her visits, she said, Wes claimed to see other people in the room. At first, he tried to make these shadowy guests go away. “But after this happened a number of times, his attitude changed. ‘They didn’t want to leave,’ Wes said, ‘so I invited them to stay.’” Wes engaged with his imaginary friends, treating them with the same kindness and respect he showed to the rest of us. “His dharma practice,” caregiver Lynn Burnett suggested, “seemed to have prepared him to sit with these confusing and uncertain realities… and his playful nature allowed him, at times, to even poke fun at this whole increasingly-questionable ‘reality’ thing.”

Wes passed from our world on July 31, 2023. I learned so much from him. But maybe the greatest lesson is summarized by an African saying he often quoted in his shows:

“When death comes, may it find you alive.”

Amen.

FYI, everyone, there was a typo in the original pasting (damn!). The ending quote was supposed to be: "When death comes, may it find you alive."

nice piece, good timing!