It was a good strategy for Seinfeld; maybe it will work here, as well. Once.

“The sun rose, our footsteps crunched the gravel, the buzzing of flies sounded like heat rendered audible. Hours passed. Hours, hours of heat and hours more, the kind of time unworthy of being mentioned even in a travelogue in which nothing really unusual seems to happen, like this one. After my trips on the Congo, on the Lena, in the Sahel, I’ve described a distillation of the hours in my books. But, at least after our youth, aren’t so many of our hours, our months, our years, like this, with only a few really memorable moments? You live a long life and end up with only certain people and events worthy of recollection.”

— From Salvation in the Desert © 2023 by Jeffrey Tayler

I remember this mindset, from my own long journey for The Size of the World:

... Sometimes nothing happens. Sometimes you sit in the bus with your head sagging backward over the greasy headrest, or contorted against the window with your cheek sweating and the low sun tracing the capillaries at the back of your eye. Home Alone or a Mexican comedy rolls across the video screen, and once in a while you open an eye to see Cantinflas take a pratfall or Joe Pesci suffer a groin injury. Children invade the bus selling oranges, Chiclets, fluorescent-green soft drinks in plastic bags. Time passes.

My life has felt a bit like that since my solo show, now three weeks ago. The lead-up to those performances was frantic preparation in service of a well-defined goal; now that the show is behind me, my next project is to bring The Size of the World back into print. But the process has been fraught with technical difficulties and frustrations.

So the past two weeks have been a fallow spell, with few footholds for my imagination. There’s much I’d like to do (see the Wayne Thiebaud show at the Palace of the Legion of Honor, the Ruth Osawa retrospective at the SFMOMA, and visit Tomales to report a story for Craftsmanship) but I can’t give myself permission to do those things until the book is out of my hands. I’m not a parallel processor, I’m serial: I must tackle major projects one after the other, as opposed to working on several at once. Don’t know why this is; it’s just how I’m made.

In an effort to tack my sails and escape these doldrums, I turned to my colleague, sometime mentor and Himalayan Writers Workshop colleague Laurie Wagner, whose vocation is guiding writers toward expressing their innermost thoughts.

Over a rare drink (my PD meds don’t love alcohol) and blackened fish tacos at Oakland’s posh-adjacent Lake Chalet, I asked Laurie for a prompt: a line from a book or poem that might dispel my reluctance to do anything creative until the The Size of the World is launched. Her thoughts turned to a couple she knows up in Occidental — two artists, Ene and Scott — who (among other creative ventures, pictured at The Wow Haus) collaborate on functional, often whimsical public sculptures, and have made a deliberate effort to structure their lives around creativity and happiness. The prompt Laurie gave me was based on a talk that Scott and Ene had once given: What Makes a Good Day. “It was about how we frame our practice at the scale of the day,” Scott told me, “and keep things grounded and in perspective while also inventing new structures and modes of interaction.”

What does it take — given the Parkinson’s-related hurdles I face — to ‘make a good day?’ Where does my needle of happiness point during the ebbs and flows of each day’s “on” and “off” spells, as my self-medicated dopamine levels rise and fall? How can I make a ‘good day’ at this age, in this body, in an unraveling world that seems an apt external metaphor for my own internal process?

Approaching that question was harder than I’d expected, and the answers probably change day-to-day, but here goes:

How to Make a Good Day

— Throw off the covers at 7 a.m. and feel the chill. Surrender that last moment of rest and warmth before committing myself to the day’s first attempt to stand up straight.

— Do not pick up my iPhone. Do not look at the news. To do so is to immediately release cortisol and adrenaline into my bloodstream, and reset my brain from a night of deep dreaming to the existential terror of a cornered mouse.

— Swallow my Sinemet at the right time (beginning usually at 7 a.m.) to ensure that each of my daily doses will kick in when I need to be at my best: playing ping-pong, biking through the graveyard, sitting through three hours of Mission Impossible at the Grand Lake Theater.

— No protein for an hour. Then: fresh fruit, coffee, yogurt, bagel, or sometimes one of the miraculous pastries from the Forma Bakery on Telegraph.

— Map out the day, hour by hour. Succumb to my OCD, and make a list of everything I hope to do before the sun goes down— from answering emails to riding my eBike; from calling my mother (who just turned 93, God bless her) to knocking off the day’s editing gigs.

— Fill my work space with music (instrumental; everything from The Straight Story soundtrack to Bach’s French Suites and (today) Iranian oud music. And the juniper aroma of Tibetan incense, which always brings me home..

— Write, with as much joy and inspiration as I can muster, Even if it’s an outside editing gig, the work at its best always feels like a game, or an intricate jigsaw puzzle. As my artist/writer/inventor friend David McCutchen once reminded me, “If you’re not having fun, you’re not doing it right.”

— My second Sinemet. Early afternoon session of Pilates near Lake Merritt, or Ping-pong at the North Oakland Senior Center. Win or lose, it’s what my body needs.

— After a simple lunch (often a turkey/avocado/Havarti sandwich), slather my inner thighs with Chamois Butt’r and limp down the block to my storage space, where my Trek eBike awaits the daily ride. Pedal hard and fast for about eight miles, listening to The Daily and/or Pivot, Making Sense, Ezra Klein, Talk Easy, Song Exploder. Yes, there will be cortisol, but this will keep it from pooling in my system.

— By now it’s about 4 p.m., and the day should be about as good as I’m going to make it. I can look at the newspaper now.

— Evening activity: Community and friendship. I live alone, but almost never eat dinner alone. It sounds strange to type out these words, but it’s fair to say that friendship is my “hobby,” on the order of gardening or mastering a musical instrument (neither of which I currently do, sadly). I devote more of my intent and attention to cultivating my beautiful friendships than I do to anything except writing. This is my gift, and my friends are my sustenance.

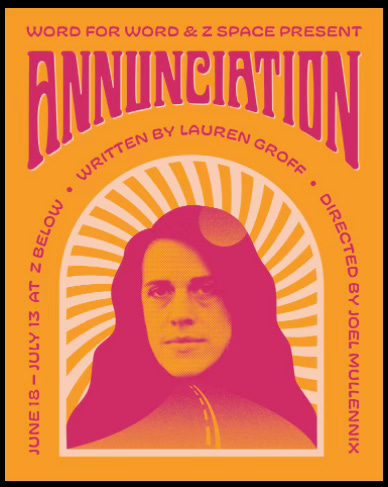

The three best things I’ve done this past week: A visit to a friend’s land in Mendocino, 12,000 acres of rippled golden hills, old-growth redwoods and streams; the hypnotic Indonesian rhythms of Gemalan Sekar Jaya at the new Svendsen Maritime Park in Alameda; Word for Word’s breathtaking production of Lauren Groff’s short story Annunciation, at the Z Space Theater on Florida St. in San Francisco.

— To bed, usually by 10, alone (none of my friends are lovers), and read for an hour and a half: two books, one fiction (currently Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, by Gabirelle Zevin) one non-fiction (currently Salvation in the Sahara by Jeffrey Tayler) and a magazine (the New Yorker, and sometimes the AARP magazine).

— A time-release Sinemet, a quarter of an Ambien, earplugs, and a silent prayer of gratitude for the day now passed, and reflection on the fact that if I do not awake, it’s been a good day. And I’ve made a good life.

The writer Jeffrey Tayler, who I quoted at the beginning, was diagnosed in 2005 with Multiple Sclerosis (MS). So I feel a kind of neurodegenerative brotherhood with him. I’ll end this offering with another excerpt from Salvation in the Sahara:

I now indeed felt that I had a future. Just exactly what kind of future I could not say. I was reluctant to make plans on which MS might impose a veto. Yet grief and regret had loosened their hold on me, having succumbed to an exorcism of solitude, of nocturnal cold and daytime heat, of sandstorms and thunderclaps. What replaced them was peace.

I had always assumed that having survived my journeys down the Congo and Lena Rivers, I could take anything, and that those voyages had afforded me a test of my mettle with lasting validity. I now understood that one needs to test one’s mettle repeatedly. Neither physical nor spiritual strength can be stored for later deployment.

Thanks for reading. And — if you are so inclined — please share, in the comments section, one of your strategies for “making a good day.”

Most of our lives are lived in these small moments. We're not Hollywood celebrities. The day to day movement of our lives are quiet and simple and ordinary. Maybe we can get to a place where we appreciate just that. What a relief. Love love.

For me the day is better when I get out in nature for extended periods *without* looking at my phone. Even an hour riding the back roads of west Sonoma Co is enough, or a 2-mile walk up and down the hills of Helen Putnam park. Also bring the travel mentality of openness to whatever may arise even when I'm home.